|

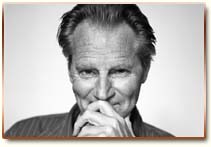

Surely it would be blasphemy to suggest that the

strongest suit in Sam Shepard’s fecund, polymath deck is

his prose. His plays have won him the Pulitzer (“Buried

Child”). His acting has garnered an Oscar nomination

(The Right Stuff). His direction on stage and screen is

highly respected, or better. But it is the

stories—seemingly attended to by readers only faintly,

as a side project or stepchild—where we find the purest

expression of the great writer’s mythos, yearnings and

toil.

His latest entry into this canon, “Day Out of Days,”

continues the turbulent cross-country scribbling pattern

of flight described by a Shepard-ish (male, actor, 60s)

character as he flees to and from his lover, pursues and

recoils from his childhood home, attacks and then

retreats from the many tent-poles of American

manhood—freedom, risk, independence, adventure, success

and fatherhood. Composed of a series of jottings, poems,

incantations and meditations, some no longer than a few

lines, the book feels like a magical mixtape of little

hymns dreamt by the recurring hero of Shepard’s oeuvre

including “Great Dream of Heaven,” “Cruising Paradise,”

and “Motel Chronicles.” When he was interviewed during

the production of his play, “The Late Henry Moss,” for

the movie This So-Called Disaster, Shepard was asked

what career path, other than his own, he would rather

have chosen, he answered immediately, without a moment’s

pause, “Musician.” So perhaps it is natural that the

drummer and guitarist who has said he conceives of his

plays the way a musician does a song, would have found

such an arrangement of ballads.

But trapped within the amber-resin tone of these stories

is all the thrashing of a knife fight. The deeply

conflicted narrator of “Costello,” who, like Shepard,

grew up in a dusty farm town just East of LA, returns to

the now unrecognizable ‘burb (to find himself,

presumably) only to deny his identity to a high-school

chum who recognizes him from his movies. The former

classmate describes his old friend, who changed his name

(as Shepard did—from the family-given moniker Steve, to

“Slim Shadow” in the Village during the 60s, and

ultimately to Sam), as a wild hellion, stealing cars and

rampaging back and forth to Tijuana. And as much as the

present tense narrator wants to shirk that old

character’s behavior, he is doing nothing more than the

middle-aged version of his smash-and-dash youthful

excursions. At the story’s conclusion we are left to

think that the narrator will only pick up again the

headwaters of the mighty Route 66 (which did originate

in Shepard’s hometown of Duarte) and sail off again into

the unknown.

Many of the stories in this volume express a fixation

with horses, the like Shepard grew up minding, and among

which he now lives in Kentucky, and all that the wild

free-spirited beasts herald: unbridled forces; the race;

the “breaking” of a wild colt; the danger and

intoxication of the bet: the emptiness a losing ticket;

the feeling of failure that lingers long after the track

has gone quiet. Shepard is terribly attentive to the

arch themes of masculinity and here he has found a

resounding mythological metaphor for the many sides of

man—as the oppressor and the oppressed, the vital and

the objectified. Horses are ghostly apparitions

throughout the stories which the author allows to

quicken in the reader’s mind, a latent image growing

stronger on paper in a developer bath.

And the achievement of such archetypal heights comes by

a well-considered process, one that we feel we might be

able to glimpse throughout the book in its nude

construction. From the beginning there are distinct,

direct links to Shepard’s own life in the stories and

characters and we are tethered to a concrete reality

(allowed, even encouraged, to picture Shepard himself in

the main rôle). In “Normal,” for example, there is

description of his 2009 incarceration for a DUI. Both

“Black Oath,” and “I Can Make a Deal,” describe

intimately the struggles of alcohol dependency, while

“Wisconsin Wilderness” goes at, among other things,

nicotine addiction and tethers together a series of

stories pertaining to an “’almost’ heart attack” Shepard

suffered in truth. There are too the geographical loci,

of Minnesota and Kentucky where he now lives,

throughout. So we begin seated in—and revisit often—this

recognizable, almost confessionally accurate, world. We

see, in the first story “Kitchen,” for instance, in a

very closely rendered self-portrait, the writer at his

work table in his kitchen, staring at photographs,

talismans of he remembers not what, allowing his

imagination to take flight into other realms of

reality—into realms of absurdity, surrealism, macabre.

It is as if we can listen to, in real time, the author’s

mind as it begins taking in its surroundings, like the

pulsing vein in his ankle (“Circling”), and then coils

upward, along the arabesques of smoke through

traditional fictive encounters (with an old love in

“Indianapolis”), up to metaphorical resonances and

images from wild dreams like mercenary who cuts off a

finger by way of atonement for past deeds or the

unforgettable skinned face an assassin tries to submit

as an invoice for his job.

Though the entries are linked by little other than

Shepard’s tropes and tone, there are two ongoing stories

we return to from time to time with narrative updates

(one of these, a buddy comedy road trip with three guys

fleeing their wives in a generally Southwesterly

direction, in a vague search for adventure, fizzles and

disappears almost without our noticing). The more

powerful is the story of a man who discovers a severed

head in a roadside ditch and is commanded by same head

to escort it to the nearest (thought it is not that

near) lake to toss it in and thus put at rest. It will

surprise no avid reader of Shepard that the head may

possibly be that of the man’s father and that his quest

to rid himself of it has metaphorical overtones. Much,

if not all, of Shepard’s work is a dance around his fear

that he would become his violent, alcoholic father and

this book is no different. There are in its pages a

blunt description of his father’s death by vehicular

manslaughter in Bernalillo, New Mexico, a recitation of

the narrator’s efforts to arrange his patterns of speech

and walk in blatant distinction from his father’s,

comparison of his father’s traumatizing military service

with his own performances as military men in movies,

and, toward the end, a sort of realization that he would

not, could not ever be his father.

It is a beautiful and heartbreaking and sensuous

consolation even if neither the narrator nor the reader

will ever give up worrying, writhing or struggling. It

is merely a chapter break in the rough, nostalgic

saga-slash-elegy wrought by one of America’s greatest

men of letters, and another reminder that what drives us

will destroy us, that what we run from we return to,

that the brutal in his literature is the beauty of Sam

Shepard’s creation.

It is a reminder that we will never stray far from the

lonely highway of his words.

|