|

|

|

NEWS: December 2017 |

|

|

|

December 30, 2017 |

|

Oklahoma's Carpenter Square Theatre opens the New Year with "Ages

of the Moon", one of Sam's last plays. The comedy-drama about two old

friends plays January 12-27, 2018. All performances are at the theater, located

at 800 W. Main in downtown Oklahoma City. "Ages" continues some of the themes

that have been ever present in Sam's work, such as the troubled and comical

sides of family life, friendships, and experiences of love. Byron and Ames are

old friends reunited by mutual desperation. Ames has retreated to an old shack

to lick his wounds after his wife kicked him out of their house for some

adulterous indiscretion he can’t even recall. Over bourbon on ice, they reflect

and bicker until fifty years of love, friendship, and rivalry are put to the

test at the barrel of a gun.

Terry Veal directs with assistance from Michael Greene as

stage manager. Rob May and Michael Kramer co-star as Ames and Byron.

Reservations are highly recommended for the intimate 90-seat theater.

Visit www.carpentersquare.com for more information.

* * * * *

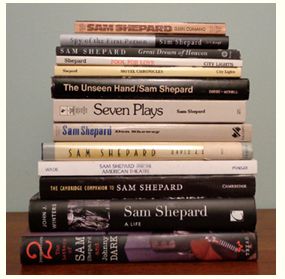

Counterpoint Press has announced that "Sam Shepard: A Life"

by John J. Winters will be published in paperback in March. It will include an

epilogue recounting Shepard's last days, the many tributes that poured in, and

more. Upon Sam's death last summer, John issued the following statement:

I was in Chicago when word reached me that Sam had passed.

Though I'd heard that his health had been failing for some time, the news

somehow surprised me. I never doubted that when it happened it would bring me

great sadness, which it did.

Sam will be remembered as an American original. He was an important American

writer, one of the greatest American playwrights of the past half century, and

as an actor he graced the screen with an authenticity that was always coupled

with a surprising vulnerability. To encounter his work in any medium meant never

forgetting it.

I hope my book will remind people why he mattered, and with any luck, will be

around to tell future generations about this talented and versatile artist. I

believe he will be well remembered for many generations, if not longer. As one

of the many saddened commentators following Sam's obituary in the Times put it:

"Punch a whole in the sky, Sam." I'll add only, God speed, and thank you for the

words and images.

* * * * *

Dustin Illingworth, LA Times, book review:

"Spy of the First Person" is an eloquent, if necessarily brief,

valediction. At just 96 pages, its effect is one of atmosphere rather than

narrative, an aching requiem sung in the shadow of extinction. It is also partly

autobiographical. Like Shepard, the narrator is an old man dying of a

debilitating illness. His flickering consciousness ranges over great temporal

distance, blending present-day observations with fragments from a disintegrating

past.

From the NY Times, 12/29/17 - Deaths in 2017:

Pillars of the theater fell: the directors Peter Hall, who towered on both

sides of the Atlantic, and Max Ferra, who championed the work of Latinos; the

British actors John Hurt, Roy Dotrice and Alec McCowen; and the playwrights A.

R. Gurney and Sam Shepard, though “playwright” alone does little justice

to the uncontainable Mr. Shepard’s manifold artistry, which branched as well

into movies, television, music and fiction.

* * * * *

Mick LaSalle, SF Chronicle, 12/29/17 - 2017 in Review:

Sam Shepard: We had other notable movie deaths — Jerry Lewis, in

particular — but before Shepard became ill, he was at the top of his game. Thus,

at 73, he was a real loss to the art. He thought of himself mainly as a

playwright, but his acting was hardly a sideline. He had a philosophical quality

in his very being, a kind of courageous acceptance of the truth, and an honesty

that called forth honesty in others. He was a convincing hero, and as a villain

he was terrifying, because he still maintained his familiar aura of moral

certitude. Nothing could dissuade him. Sam Shepard was a great actor.

When Sam died in July, LaSalle wrote the following: "'I

didn’t go out of my way to get into the movie stuff,' Sam Shepard once said. 'I

think of myself as a writer.' And in the end, it’s as a playwright that Shepard

will probably be most remembered. But then again, maybe not. Plays have to be

produced and rehearsed and presented to the public. But movies are everywhere,

and Shepard not only made a lot of them, but lots of very good ones spread out

over three decades. He distinguished himself in these films as a strong and

distinct screen presence."

* * * * *

Michael Cavna of The Washington Post wrote, "From

music to movies, we mourn pioneers and performance icons in 2017." As a memoriam

for a way to say "thanks", he posted this work from the Comic Riffs

sketchbook.

|

|

December 29, 2017 |

|

The New York Times Magazine featured an article on those who

had died this year. The photo below was labeled - "The writer Sam Shepard's hat,

at his son Walker's home in Louisville, Ky". The quote is from his other son

Jesse.

"He was always a pinch-front kind of guy, the style is kind

of a triangular crease in the front. It’s a strong reminder of the man — of him

being outside and on location and involved in the day. There is a practicality

and a confidence to it. It’s a well-worn hat. His work was key to his day and it

was always about process and project. I was a wrangler on Silent Tongue;

it was my first job. I briefly doubled my dad on Don’t Come Knocking

because the production wouldn’t let him run a horse hard because he might get

hurt as the star. It was the last location work I did with him."

* * * * *

In a recent podcast from Playback, director Scott Cooper

discusses his latest film Hostiles, but also talks about his relationship

with Sam having cast him in Out of the Furnace. After being given

the script, Sam called Scott from Paris and said, "Well, this seems like a

cousin to Buried Child". After filming, their friendship continued and

they stayed close. Sam described the two of them as "two peas in a pod". The

kindred spirits would often converse on horses, politics, literature and discuss

their individual projects. In a recent interview with GQ, Scott talks about his

younger days - "I was afflicted with a certain wanderlust. You know, wanting to

travel and this kind of idealism of a vagabond lifestyle. Which I never really

did lead. But it sounds great when you read Sam Shepard. One of my former pals

and mentors."

Scott then tugged on his denim jacket. "Sam gave me this coat," he said. "I had

commented to him on many occasions how much I liked it on the set because I did!

Sam was probably the most effortlessly cool person I've ever been around. And

his work spoke to me on a very deep level."

Scott Cooper wearing Sam's jacket *

* * * * Author Howard Norman has contributed his

remembrance of Sam at this link and

concludes, "To me his writing will, for a

long, long time, continue to dignify literature." |

|

|

|

December 24, 2017 |

|

Liz Nord, No Film School:

RIP: 17 Film Luminaries We Lost in 2017

These influential figures will be missed by the film industry and beyond. One

comfort we have as creators is that, after all the toil and trouble we go

through to put our work out into the world, that work has the potential to

outlive us and continue to move people long after we are gone. That can

certainly be said of the people on this list. From genre-defining directors to

DPs who made us see the world in new ways, here is one of the names that we hold

close to our hearts from those who left us in 2017.

Sam Shepard is the type of artist who will be remembered across every discipline

of culture. While the plays he wrote (44 in total, three of which won Pulitzer

Prizes) are some of the greatest contributions to American theater, the themes

that sprouted from his mind have gone on to inspire generations of filmmakers,

actors, and writers to delve into the darker side of family life, friendships,

and experiences of love. He was also a well-respected actor, garnering an Oscar

nomination for his role as Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff (1983).

* * * * *

Here's a page from a PDF of the Midway Messenger:

|

|

|

|

December 17, 2017 |

|

Sam's pal Johnny Dark has been silent since his

friend's death and many of us wondered what his thoughts were, especially since

the film "Shepard & Dark" had revealed their relationship ending on a rather

sour note at that time. Today UK's Guardian posted Johnny's remembrance of Sam,

and typically he exposes some raw edges in their 54-year friendship. I like

Johnny because he doesn't believe in bullshit.

We first met in 1963 in New York’s Lower East Side when it

was a neighborhood of actors and theatres and artists. He was introduced to my

wife, who had two daughters, and he married the eldest [the actress O-Lan

Jones]. We hit it off right away: I liked him very much. He was 24 years old and

in the early stages of writing plays, and he was getting some recognition. He

was very unpretentious and friendly, and he was always like that, up until the

end.

Then my wife and I left New York, and when Sam and O-Lan came to California to

visit us, we all decided to live together as an extended family. We took a

series of houses and lived together for about 15 years with Sam, his wife and

son, O-lan's younger sister and my wife. We were in our late 20s, early 30s; he

was three years younger than me. It was unusual to have another male in the

house – my son-in-law – who was also a best friend. For their little boy Jesse,

it was an unusual set-up to grow up in, but he only realized that years later

when he met his wife’s family, which was much more conventional.

Sam and I got up to a lot of mischief. He was starting to write some of his

best-known plays at the Magic Theatre in San Francisco, so we had a lot of

opening night adventures. We had motorcycles and we raced around, we travelled.

I was a writer and he was a writer, and we both loved movies. He was an

alcoholic and I was a drug addict. And we had an inflated sense of how wonderful

we were.

It was during this time that he was first approached to be in

a movie. Bob Dylan called to ask him to go on the road with the Rolling Thunder

Revue to do some writing for a movie they were making. And on the basis of that,

the director Terry Malick called and asked him if he would like to be in "Days

of Heaven", with Richard Gere, an unknown at the time. That was his first

experience in the movies, and from there he had a dual career as a playwright

and a movie actor.

But what happened is he ran off with Jessica, which was a big upheaval. One day

he just didn’t come home. Everyone was surprised except me. They started a life

together, and eventually had two children. We started to write letters to each

other because he lived in various places, Virginia, Minnesota and New Mexico. We

were both big letter writers: we’d write about women, drugs, various stories.

And we’d talk a lot about literature: his main man was Samuel Beckett, mine was

Jack Kerouac. He read a lot of plays too – Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde.

We were friends in our 20s, 30s, part of our 40s, and then he fell under

Jessica’s influence to a certain extent. He started going through a change

there. And you have to factor in the tremendous effect that becoming famous

through movies has on a person. It’s a terrible influence. Wherever you go, the

whole world is giving you special treatment, and that’s a very damaging thing

for the ego.

I was never particularly interested in his plays: they were filled with humor,

but also with violence and chaos, so it always amazed me that people were

attracted to him based on his plays. He drew another audience through his

movies, and that was outstanding. He was a very handsome, popular young man. It

was a form of mass hypnosis. He played Chuck Yeager in "The Right Stuff", the

man who broke the sound barrier, and people thought Sam broke the sound barrier.

One of the things we had in common was that we were very private people. We were

both loners, and when we got older, it became more intense. He had a very

difficult time with relationships. He left his first wife, he ended up leaving

Jessica and the kids, and living alone on his ranch in Kentucky. His love before

anything else was writing. He was really a lost soul, looking for something

impossible. He couldn’t maintain relationships at all. Even when he was with

Jessica, he bought a place that was far away so he could run off from it all.

Ever since I met him, he was running away. And he described himself like that to

me. Restless. Discontented. Lost. Those things don’t matter that much when

you’re young, but when you’re older, they become more and more difficult.

When Sam came to visit me in Deming, a little town near the Mexican border, he’d

check into a motel and call to tell me he was in town, and we’d meet every day

in a local road-side restaurant. We’d sit for hours, talking and reminiscing.

Until the end, when he started getting sick: he had ALS and emphysema. He even

had trouble lifting his cup to his mouth at that point. So mostly what we talked

about was his illness. He was driving around the country seeing if he could find

some kind of cure for it.

That was difficult. He knew he was dying. There’s no cure for either disease:

they get progressively worse. From what I could see he was getting more

depressed, more angry, going through all the stages people go through when

they’re dying. He had been busted for the second time driving drunk. All of

these things were happening at once for him. His life was falling apart.

The last time he came through here he was having a lot of trouble driving. He

shouldn’t have been driving at all. He was losing control of his whole upper

body, having trouble controlling the truck. He was driving to his farm in

Kentucky, travelling with a large oxygen machine because of his difficulty

breathing. The morning he left I had to load the machine on the truck and all of

his medicines, and he just got into the truck and drove off. I took a load of

pictures of him that morning and they may be the last photos ever taken of him.

So it goes from the light in the 60s, and youth, to the dark at the end. He had

a great need to be adored and applauded. I have some of that too. We were very

similar in a lot of ways, but we had very different styles in the way we dealt

with each other and other people. He was a big influence on me, in a good way

and a bad way. He was a big part of my life. |

|

|

|

December 11, 2017 |

|

Patti's tribute to Sam last Tuesday in celebration of his book release was

written up at this

Vogue link. It's a great overview of the evening by Rebecca Bengal. In

the following, she describes Patti: "Taking a seat on the edge of the

stage as her longtime collaborators Lenny Kaye and Tony Shanahan played a

rendition of the folk ballad 'Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie' —a cowboy lament

for the man with the cowboy mouth—she rocked to its loping rhythm and seemed

briefly overcome. Then she caught herself, flashed a warm smile to Shepard’s

three grown children, Hannah, Jesse, and Walker, seated in the second row." And

later in the evening, Patti tells her audience, " We were friends for more than

half a century." The photo below is one of my favorites:

A few more reviews of "Spy of the First

Person" have surfaced this past week. Sam Sacks of The Wall Street

Journal quotes the old man in the story - "The thing I remember most is being

more or less helpless and the strength of my sons." Sacks writes, "At last he

has no choice but to accept the company of others as he travels through the wide

American somewhere." Yes, the lone cowboy needs someone to scratch his itch or

wipe his ass. Biographer John J. Winters, who wrote "Sam Shepard: A Life",

refers to Sam as the "wounded cowboy" who retires to his Kentucky home to await

death. In

his review, Winters writes, "When the doctor tells him there’s a

problem, his response is pure Shepard: 'I know something is wrong. Why do you

think I’m in here? He just looked at me with a blank stare.'" Reading that, I

can feel an icy wind sweeping over my face and it feels prickly...

And Winters goes on to point out an observation that no one

else thus far has mentioned. He writes, "Shepard’s last written reflection is,

appropriately enough, about fatherhood, something he’d dealt with in life, on

pages and stages, for more than a half century. However, notably missing from

'Spy of the First Person' is any mention of his own father."

How true, but what about the glaring absence of a certain

woman who was the love of his life for almost 30 years? She's missing from the

pages of this "fictional memoir" and her presence is missing from his final

weeks on his deathbed, but at least brave Patti Smith/Mighty Mouse arrived to

save the day. As you can witness in the documentary, "Shepard

& Dark", perhaps Sam never had the courage to address those painful

issues that were too close to his heart, not even at the end of his life. |

|

|

|

December 6, 2017 |

|

Last night Patti Smith performed at a tribute concert

for Sam in celebration of the release of his book. The event took place at St.

Ann & the Holy Trinity Church in Brooklyn. During a performance of "Dancing

Barefoot", Patti forgot one of the lyrics and began laughing. "What is it? I've

sung this nine million times," she said. "You know what, Sam really liked when I

did this. He would actually taunt me and be somewhere and get my attention so I

would mess something up. And he had this coyote laugh, I can't explain it. So

I'm sure he's enjoying this right now."

|

|

|

|

December 5, 2017 |

|

Guess how I spent this afternoon? Yes, reading "Spy of the

First Person". We'll call my thoughts "Musings by Coymoon". Let me preface this

by saying except for "The One Inside", I have thoroughly enjoyed the stories of

Sam Shepard, and even more so when they were narrated by him, such as his

audiobook, "Cruising Paradise". In this last volume of his work, I find a man

completely absorbed in the physical deterioration of his body without any

reflection on life and death.

These stories, often fragments, equate to nothing more than

dream sequences that we all experience. As Jocelyn McClurg (USA Today) points

out, "The reader must follow the flow; but, like trying to decipher someone's

dreams, it's not always easy." Shall we call in Dr. Freud? Except for the last

two chapters of this sparse book, there's nothing significant or meaningful and

what you'll find mostly on these pages are the ramblings of any old man obsessed

with the restrictions that his illness has brought upon him. Nothing more.

However, I believe I did recognize his friend Johnny Dark and wife Scarlett [Olan's

mother].

Wouldn't "love" be a word that would frame your remembrances

of someone? Wouldn't "death" be a word that could be better defined as you

"stand on the edge of life and see the Darkness"? [The Seventh Seal]

I am a stickler for writing reviews for books, film [Roger Ebert being the

worst!] or theater without giving away the plot or without including way too

many quotes. If you go read through the many reviews, you probably have already

read this book! Truly! * * * * * I always

wanted to take this photo

|

|

|

|

December 4, 2017 |

|

Tomorrow "Spy of the First Person"

will be released and I expect my edition to arrive shortly thereafter.

Presently, the

EW web site is featuring actor Michael Shannon reading

an excerpt from the audiobook. Shannon appeared with Sam in "Mud" and

"Midnight Special." In addition, the actor performed in several of Sam's plays.

This year alone, he participated in a June reading of "Curse of the Starving

Class" and acted in a five-week run of "Simpatico" at the McCarter Theatre

Center in Princeton, New Jersey.

When "The One Inside" was published, I indicated my dislike

of its cover with a photograph by Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Dark

and depressing. Here again is another of her images called "El señor de los

pájaros en Nayarit (1984). Tibetans believe vultures are angel-like figures that

will take the souls to heaven, but in the bible, when blessings and curses are

given to Israel, God warns them, "Your carcasses shall be food for all the birds

of the air and the beasts of the earth, and no one shall frighten them away".

Under this curse, the gathering of the vultures symbolizes the height of defeat,

disgrace, and personal insignificance, when no defenders are left to keep the

scavengers from tearing a human body apart just as they would a dead animal.

What is Sam trying to say?

In an inversion of a typical dedication page, where the

author often thanks his or her family, "Spy of the First Person" is dedicated to

the author himself: "Sam’s children, Hannah, Walker and Jesse would like to

recognize their father’s life and work and the tremendous effort he made to

complete his final book."

And obviously it was a struggle for our writer to finish his

last work. When using his typewriter became too difficult, he wrote out his

notes with pen, and when that became impossible, he used a tape recorder.

In the end he simply dictated his words to his daughter Hannah or his sisters

Roxanne and Sandy.

Knopf editor LuAnn Walther says, "People think of Sam Shepard

as the solitary cowboy of American myth riding off into the distance, but in

truth, he was dedicated to his family his whole life." I beg to differ. Does

this include his parents? All his children? Have you ever seen a photo of

Sam with his sisters? She continues, "He was adamant that he didn't want the

book to be categorized as a novel even though he was told it could create

marketing problems. He said, 'why does anybody need a label.' You have to

remember that Sam was always adamant through the years that he would never write

a memoir. But what about a memoir of his dying?

Hannah says, "The line between fact and fiction in his own

work was always very ambiguous to Sam, I believe. Many things blended together

for him." Note that she refers to her father by his first name. And again when

she states, "Sam was suspicious of technology, and the failure of these devices

and computer programs just confirmed his lack of faith in them, I think.

Recording was a very different experience for him than the physical act of

writing, and he found it somewhat disorienting, but adjusted."

He made the final edits just a week before his death,

dictating small changes to his daughter as she read the manuscript to him, start

to finish. "Some of the funniest lines in the book, in my opinion, he added in

our last edit," Hannah says. She chooses not to point out which lines. "I would

rather keep this personal, as a memory between me and my father."

In a March 2010 interview with The Guardian, Sam opened

up a bit about his only daughter. He revealed, "I never thought about having

a daughter and then I had a daughter and it was a remarkable thing. It was

very different from having a son and your response to it. With a son, it's

much more complex. And it's probably because of my stuff in the past. With a

daughter, I was surprised at how simple it is." It's to her, he says, that

he intends to leave his notebooks, "because she's the one who's asked for

them."

|

|

|

|

December 2, 2017 |

|

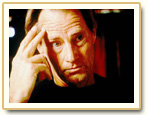

In 1998 PBS' Great Performances presented a television

special by Oren Jacoby called "Stalking Himself". The documentary

emphasized Shepard’s identity as an "odd, contradictory presence on the American

cultural scene."

"He’s well-known but unknown, handsome and seductive but willfully remote," Will

Joyer wrote in a New York Times review of the film. "He’s almost too easily the

archetype of the authentic American, at home in the wide open spaces but not

really at home anywhere."

In the documentary, Shepard also said he was uneasy about

being too easily pinned down as a character he’d played on TV.

"I think we’re faced with a dilemma now that’s terrifying. You can just get rid

of you altogether and make you an image," he said. "In fact, we prefer the image

to the human being. We’d rather watch you on television than talk to you."

I think that's a very interesting observation and certainly

applies to him.

After Sam died, filmmaker Oren Jacoby spoke about the difficulty in making this

documentary:

"It was my first time working with Bob Richman, already

highly regarded as a cinéma vérité cameraman. Still, it was a shock when we

started shooting a rehearsal on our first day and Bob kept filming our main

character (Sam) from behind or the side, always at a distance, and mostly

pointing his lens at the other people in the scene. After a few minutes of this,

I started first to whisper and then physically to try and nudge him around to

the front, so we could at least see both eyes of the man our film was about.

'Trust me,' Bob said, 'he doesn’t want me there.' It was as if he had some

special cameraman radar and was picking up a vibe that there was this invisible

line that should not be crossed. (Bob told me recently that Shepard was the

hardest and 'most private' subject he’s ever dealt with in all his years

shooting documentaries.)

"But we respected that line and slowly, over the months that followed, we gained

Shepard’s trust (or at least resigned acceptance – or maybe he just forgot we

were there!) and Bob was able to move around and film him from the front. Then,

one day, after repeatedly putting off our request for a one-on-one on-camera

interview, Shepard turned to me and said something like, 'OK, let’s go do this.'

We found a corner near a window so we wouldn’t have to take time to put up

lights or spoil the mood and filmed an almost two-hour conversation. Shepard

went into a deeply personal exploration of his life and career, something he

never did again on camera, and something that would never have happened if Bob

had barged in front of him on our first day.

When Jacoby was asked what memory stands out for him today,

he replied:

"I remember a moment when we were filming him doing a series of plays in

New York and he was collaborating with different directors and one of them was

Joe Chaikin, who had been somebody that he really admired and learned a lot from

in his early days as a playwright. Joe Chaikin had recently suffered a stroke

and had aphasia and didn't have the same language that he'd had as a younger man

when they'd worked together. And to see how Sam was very protective of Chaikin

and kind of loved and respected him and wanted to, you know, help him still be

able to work, even though he'd been through this illness — it was just a very

tender moment watching them working together."

"And another great moment I remember with Sam is we were in a

rehearsal room and there was an upright piano in a corner, and in a break in the

rehearsal, he went over and started pounding out this amazing kind of jazz blues

on the piano, Albert Ammons or one of these 1920s Harlem piano players." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|